The OSR Should Die (Advanced Edition)

Click Here for 'Basic Edition'

Is the OSR dead yet? If you asked a couple of my friends, they would say yes: there was a body of cultural knowledge which has been rendered inaccessible (for some reason) to hobbyists who are working in the same space. What is old is new again, so now people are talking about random encounters and reaction rolls as if they had discovered them themselves like Christopher Columbus discovering the Americas. Obviously, they weren’t the first ones there and, if you were to ask my friend Ramanan Sivaranjan from the Save Vs. Total Party Kill blog, no one had left either. The OSR is not dead because he’s still there, and he still keeps up with people from the time of G+ who are also all still doing their own thing if only somewhere else. How can something be dead and alive at the same time? It could be a difference of definitions. It could also be a zombie.

An authoritative definition of the OSR is difficult to arrive at because any one definition is sure to attract contention from at least one individual or group that self-identifies with the term. These parties are not always mutually exclusive with each other, but they tend to embody particular perspectives on the term owing to their different time periods, social networks, or modes and aims of activity (including play, communication, and organization among other factors). Just as with my previous discussion of lyric games, trying to invent or assert a definition of the OSR is itself participating in the discourse surrounding the OSR; it becomes self-referential and, often, self-serving [1]. It is thus worthwhile, instead, to consider the multiplicity of the OSR as an empty signifier (i.e. a signifier that signifies nothing), to understand where and why it is invoked and to what ends do people try to answer the question, “What is the OSR?” In doing so, we can criticize not just the apparent existence of a singular and true OSR, but also the role that the mere term ‘OSR’ plays in establishing collective identities through false imagined histories.

An Insufficient History of Old-School R’s

Psychoanalysis is like the Russian Revolution; we don’t know when it started going bad.

Deleuze & Guattari, Anti-Oedipus

A history of anything is always going to be biased towards one view than another. It will be to our benefit, then, that we will not consider the history of a particular OSR or an offshoot thereof, but of the term ‘OSR’ and to what it has been applied. Although there is certainly some historical and cultural continuity between groups that identified with the OSR, they obviously existed in different contexts of time, (digital) space, and cultural activity.

In this section, I first will attempt to tell a short history of the term ‘OSR’ to point out where the online subcultures that have been called by that name developed in qualitatively different ways. I will do this with a view to “object-oriented ontology”, a school of philosophy founded by Graham Harman which emphasizes the reality of all kinds of objects, from communities to ideas, under the assumption that those objects really exist as more than the sum of their parts. Through this lens, each OSR subculture exists as its own discrete ‘object’, and the OSR as an idea is itself an object (or multiple objects) that interacts with each of these groups. Then, I will criticize object-oriented ontology to reveal that what is being considered is not a reality of immaterial objects (such as “the OSR”), but a discrepancy between a signifier imposed by language and things in the real (material, social) world. The real question is not when the ‘real’ OSR started and ended, but why that term has been used again and again by different groups with different interests.

From 2000-2009

"We have Advanced Dungeons & Dragons at home."

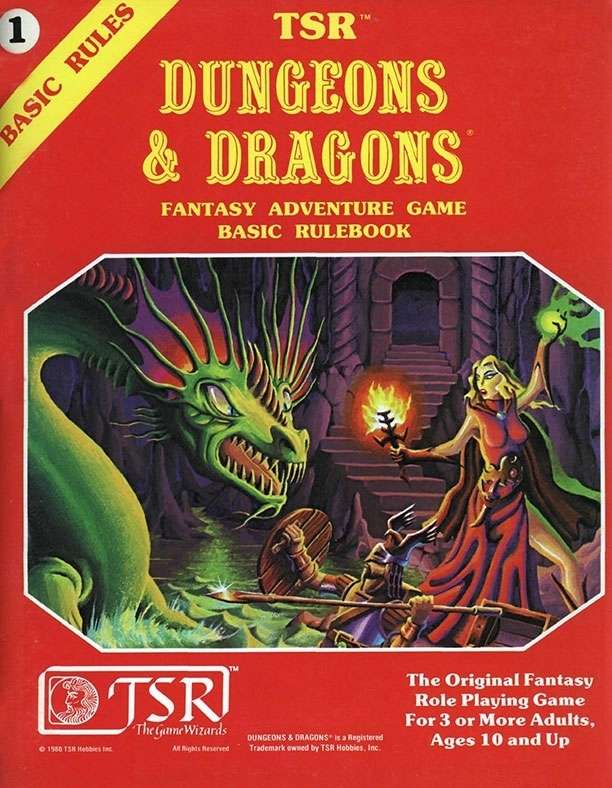

The term “old-school revival” or "old-school renaissance" originated in the early 2000s. It was used mainly by players of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons on the fan website Dragonsfoot. Dungeons & Dragons Third Edition had just been published by Wizards of the Coast, and it represented—or perhaps imposed—a new direction of play for the Dungeons & Dragons brand (albeit one which had been anticipated with the release of supplements for AD&D Second Edition, especially Combat & Tactics). Meanwhile, Dragonsfoot published materials for ongoing AD&D campaigns, and those who felt left behind by Wizards of the Coast or even the post-Gygax TSR (the original publishers of D&D) found a new home. However, many feared that without official support, the player base for these defunct games would dwindle and all would be forgotten.

Third Edition posed a problem, but it also presented a solution. Owing to the promiscuous Open Game License (OGL) originated by Wizards of the Coast for their new game, Dragonfoot’s OSR community was enabled to publish retroclones which either faithfully reproduced the rules and mechanics of early D&D rulebooks, or remixed them to agree more with Third Edition's d20 system: Castles & Crusades (2004), OSRIC (2006), Basic Fantasy RPG (2007), Labyrinth Lord (2007), Swords & Wizardry (2008). This is the end of the story for some. There are users on the Dragonsfoot forums even today.

This was also a beginning for many. James Maliszewski began his Grognardia blog in 2008. His first post was a copy of the OGL, declaring all materials on his blog to be under that license. His second post was called, “What’s a Grognard?”, where he lays out the mission statement of his blog [2]:

RPG grognards are popularly held to be fat, bearded guys who go on and on about how things were better “back in the day” before “the kids” ruined everything. I don’t think the history of roleplaying games since 1974 has been one of continual decline, but I do think a lot of good stuff has been lost or at least forgotten since then. One of the purposes of this blog is to discuss that good stuff and its importance for and applicability to the hobby today.

Never fear: there will also be grumbling, grouchiness, and complaining aplenty! I may be neither fat nor bearded, but I can rant about kids today with the best of them.

James Malizewski, "What's a Grognard?"

There is, perhaps, a shift in focus between Maliszewski’s blog and the Dragonsfoot users who first identified with some ‘OSR’. Rather than creating new materials for AD&D specifically, or creating retroclones of early D&D books (itself a shift in focus!), Maliszewski’s goal was to apply old cultural knowledge of D&D to new contexts. This shift was not an individual choice but was representative of a larger shift in the community which had identified as the OSR. The story is best told by Maliszewski himself. In 2009, he wrote “Full Circle: A History of the Old School Revival” for The Escapist, in which he explained the development of the old school revival from circa 2000 to 2009 [3]. After explaining the different retroclones that were published in 2004-2008, he explains that blogs did much of the heavy lifting for the development of culture and theory regarding campaign planning and play:

If the retro-clone creators are the “engineers” of the movement, the bloggers are its “philosophers.” They provide the rationale behind the rejection of modern rules sets and in favor of the hobbyist approach to gaming that they believe harkens back to its earliest days. It is here that controversy often arises, since the opinions of many old school bloggers are seen — rightly — as a challenge to the verities of the modern hobby, especially its increasing commercialization and detachment from its own history.

James Malizewski, "Full Circle: A History of the Old School Revival"

Maliszewski argues that the OSR “has no grand unifying principle beyond a love […] for RPGs, particularly Dungeons & Dragons” (and its older editions), but rather than being a reactionary ‘revival’, it included the creative force of a ‘renaissance’. He said that many people who identified with the OSR are simply playing the way they want to play (“rules light, freeform, and placing a greater emphasis on player skill rather than on character skill”), and doing it themselves (“DIY”) rather than receiving that play style from a book sold to them. This is perhaps best represented by Matthew J. Finch’s A Quick Primer for Old School Gaming, which outlines base principles such as [4]:

- Rulings, not Rules

- Player Skill, not Character Skill

- Heroic, not Superhero

- Forget Game Balance

Many of these maxims contradict the ethos of TSR-sanctioned play as early as the original Dungeons & Dragons and reject the advice in Gygax’s Advanced line. Regardless, because of the movement’s creative fervor and drive to establish itself, there were materials being made that were not retroclones but, instead, wholly new works that apparently share an ethos of design with those old D&D editions; Maliszewski cites Mazes & Minotaurs (2006) and Encounter Critical (2004) as particular examples, being based on Greek myth and science fiction respectively. The OSR was still in its infancy, Maliszewski concludes, and whether it will result in a renaissance proper was then yet to be seen.

Maliszewski’s article is not without rose-tinted glasses, especially with respect to the relationship between the early play culture of Dungeons & Dragons and the culture propagated as the OSR. John B. from The Retired Adventurer is correct to identify the premise of the old school renaissance as “a romantic reinvention, not an unbroken chain of tradition” [5]. This may be attributed to a shift in focus somewhere between 1999 and 2009, from continuing to play AD&D to playing according to a specific style which was then theorized about on blogs et cetera. It is not a total discontinuity, however: early on, the early members of the self-identified OSR took a DIY approach because their play styles were no longer supported by official publications of D&D. Being then a movement centralized in one online community, it was not unreasonable for one play style to predominate that community’s culture. All the while, this play style has the appearance of being something rediscovered rather than something being created, with legitimacy derived from this apparent tradition.

There is no point in arguing where a line should be drawn in time between a ‘real’ OSR and a ‘false’ OSR in 2000-2009, or between a so-called revival and renaissance. This is not only because many of the same people participated in the OSR up to 2009 and beyond, but because the tendency of the OSR to become a ‘movement’ and a ‘culture’ existed at its inception. Its origin was, strictly speaking, nothing new: it was AD&D players (less often of other editions) reminiscing about publications for D&D before Third Edition, or even before Second Edition. The production of cultural materials by this community, whether forum threads or blog posts or rulebooks, necessarily culminated in a renaissance, as the act of creation and introspection results in something new informed by past and present. The unifying principle of the OSR at any point is nostalgia for a lost ideal, the reality of which was never lost but was instead constantly in the process of being created in hindsight.

From 2010-2019

The lingua franca of a post-Gygaxian OSR. For many, as simple as it gets.

It’s now 2022, over 10 years after Maliszewski’s article. What’s happened since? Between 2011-2019, Google released the social networking platform Google+ or G+, where users could create distinct groups or communities to interact with rather than always addressing a whole mass of “friends”. This social network interfaced with the blogging platform Blogger, which Google had acquired earlier in 2003. As Maliszewski notes, blogs were increasingly popular throughout the 2000s as a way to propagate the culture of the OSR. What better way to discuss the hobby, share blog posts, and organize campaigns online? G+ became a centralized hub of activity as the OSR outgrew the original Dragonsfoot forums, perhaps both in size and in ideology. Yet it is essential to recognize that the OSR of the early 2000s, largely a revival of interest in official AD&D, was already overshadowed by an interest in other older editions of D&D and a desire to (1) fully realize the principles apparently encoded in those rulebooks, (2) create cultural materials to facilitate those principles, and (3) create altogether new materials based on those principles. This is the era many identify as the OSR (or, rather, the time to have been there), including those who participated in it.

This period produced much of the common wisdom we now often take for granted. It elaborated upon the OSR as a play style, rather than as a revival of appreciation for TSR literature. Of course, it is now mostly accessible through blog posts that were written at the time rather than through directly accessing G+ where those ideas were often originally discussed and even practiced through online play sessions. Below are many seminal posts in chronological order; I begin with some dating to 2007 because, again, these are all in conversation with each other even before G+ was launched in 2011. This is another example of continuity alongside discontinuity, as the umbrella expanded with a view towards contemporary DIY play inspired by old-school materials, rather than just working with the same older rulebooks (though with a particular interest in the original D&D and the 1981 D&D Basic/Expert [B/X] rather than especially or even AD&D).

- Cone, Jason. 2007. “Philotomy’s OD&D Musings”, Philotomy. Republished by R. Sivaranjan in 2013. An explanation of what makes the original D&D ruleset from 1974 so compelling, including exegesis and house rules. Originates the mantra “dungeon as mythic underworld”.

- Robbins, Ben. 2007. “Grand Experiments: West Marches”, ars ludi. A referee’s experience running a sandbox campaign at an open table with irregular groups of players, irregular parties of characters, and irregular ongoing ‘plots’.

- Maliszewski, James. 2008. “On the Oracular Power of Dice”, Grognardia. Referees should embrace random events and results from die-casting as a fundamental of the game.

- Trollsmyth. 2008. “Shields Shall be Splintered!”, Trollsmyth. A house rule that shields (typically +1 AC) can be destroyed in exchange for totally negating an attack.

- Alexander, Justin. 2008. “The Death of the Wandering Monster”, The Alexandrian. Wandering monsters, i.e. random encounters, pose a threat to players because they introduce uncertainty about their ability to survive any stretch of exploration. Without random encounters, the game is much less challenging.

- Maliszewski, James. 2008. "Gygaxian 'Naturalism'", Grognardia. Describes the naturalistic technique employed by Gygax in monster and adventure design, where the game's setting and inhabitants are simulated as part of a living world rather than just treating them as pure (formal) obstacles of the game.

- Maliszewski, James. 2008. "Ich bin ein Gygaxian", Grognardia. On one hand, heavy praise for Gygax's influence on the author's own view of D&D; on the other hand, an explanation of the difference between the original D&D as an engine for DIY play, versus AD&D as the authoritative word of Gygax himself. This, perhaps, prefigures the later OSR (see From 2010-2019).

- Shorten, Michael. 2009. “Dispelling a myth - Sandbox prep”, ChicagoWiz’s RPG Blog. You do not need to prepare in great detail a sandbox campaign, because the holes will be filled by whatever the players do or seek out.

- Steamtunnel. 2009. “In Praise of the 6 Mile Hex,” The Hydra’s Grotto. Hexes with a short length of 6 and a long length of 7 are the easiest type of hex for navigation and exploration, and they make sense in terms of how far the human eye can see.

- Alexander, Justin. 2010. “Jaquaying [sic] the Dungeon”, The Alexandrian. Jennell Jaquays’ module design for D&D serves as a prime example of how to make interesting dungeons to explore, by incorporating looping paths and discontinuous levels et cetera.

- Arendt, John. 2011. “The Sandbox Triangle”, Dreams in the Lich House. Sandbox can be considered an aspect of setting or of play activity. In the latter sense, you must trade off between freedom, detail, and effort (while playing).

- Campbell, Courtney. 2011. “The Quantum Ogre”, Hack & Slash. A series of blog posts about how overdetermining results for players, such as forcing them to encounter a specific thing, leads to less player freedom and less enjoyment.

- Raggi, James. 2011. “Toybox Style Play”, Lamentations of the Flame Princess Blog. A toybox is an approach to designing adventures where there is no overarching plot or other predetermined course of events, but only a location with which players can interact as they please.

- Natalie. 2012. “Why D&D Has Lots of Rules for Combat: A General Theory Encompassing All Editions”, How to Start a Revolution in 21 Days or Less. The function of combat rules in the original D&D and in B/X is to make combat deadly and thus desirable to avoid.

- Bloch, Joseph. 2012. “Combat as War vs. Combat as Sport”, Greyhawk Grognard. A summary of a forum thread on ENWorlds earlier that month, which argues that there are two different understandings of combat across editions of D&D: as war versus as as sport. The former is ‘old-school’.

- Johann. 2012. “My Trinity of Old School Gaming (Part 3)”, Out for Blood. The author explains three cyclical aspects of what he considers old-school play: quick character generation, simple and exciting combat, and a high mortality rate.

- Macy, Joshua. 2012. “XP for Loot in D&D”, Tales of the Rambling Bumblers. Receiving XP for treasure looted from a dungeon results in a different drive for play than receiving XP for killing monsters; the former leads to more creative and interesting play.

- Jack. 2012. “Matt Rundle’s Anti-Hammerspace Item Tracker”, Rotten Pulp. An abstract inventory management system based on containers of discrete slots, to explicate where exactly characters are holding or carrying their items.

- Campbell, Courtney. 2012. “On Set Design”, Hack & Slash. An explanation of how to write room descriptions using tree structures with more detail (and treasure) on lower levels of the tree, accessible upon closer investigation.

- L., Gus. 2013. “Thoughts Regarding Character Mortality and Old School Dungeons and Dragons”, Dungeon of Signs. Classic D&D is not about high lethality, as much as it is about the party as the subject of play where characters are merely instruments thereof. It is a cooperative game at its core.

- B., John. 2013. “A Procedure for Wandering Monsters”, The Retired Adventurer. An elaboration upon the wandering monster check, introducing a new schema where a wandering monster means rolling for an encounter, a lair, a spoof, tracks, or traces of the monster.

- S., Brendan. 2014. “Overloading the Encounter Die”, Necropraxis. The encounter die, which in B/X was a 1-in-6 chance of a random monster every 2 turns, can be expanded to include more outcomes indexed to other rolls of the die. This way, the entirety of the dungeon crawling game can be emulated through random outcomes.

- L., Gus. 2014. “Towards a Taxonomy of ‘Trick’ Monsters”, Dungeon of Signs. An explanation of unique monster abilities and categories thereof, which can be used to challenge players beyond just counting hit points.

- S., Brendan. 2014. “Hazard System v0.2”, Necropraxis. Extends the functionality of the overloaded encounter die into new contexts of play activity, creating analogous procedures for them.

- Schroeder, Alex. 2015. “Introduction [to Sandbox Play]”, Alex Schroeder. An old-school dungeon crawl uses rules from 1980s editions of D&D and takes place in a mythic underworld, as per J. Cone; the campaign is not planned out but is determined by the actions of players.

- Kemp, Arnold. 2016. “Dungeon Checklist”, Goblin Punch. A checklist of seven things which a dungeon needs in order to be desirable and interesting to explore for players. The first item on the list is “something to steal”.

- Kemp, Arnold. 2016. “‘Rulings Not Rules’ is Insufficient’”, Goblin Punch. The old-school mantra “rulings, not rules” obscures how system is not the only factor of play experience, but also: the adventure, the referee, and the players. Creative play must be encouraged on all these levels, not just in rules or a lack thereof.

- Manola, Joseph. 2016. “OSR aesthetics of ruin”, Against The Wicked City. Old-school settings tend to have motifs of post-collapse and societal decay, which contributes to the community’s preoccupation with horror tropes and also gives player-characters good reason to freely explore the game-world.

- L., Gus. 2016. “Monster Design and Necessity”, Dungeon of Signs. An explanation of the random encounter tables in the original D&D, and how the implicit categories of power and intelligence can be used as a basis for new encounter tables.

- Manola, Joseph. 2016. “Old-School Space vs. New-School Time”, Against The Wicked City. Whereas new modules have predetermined plots of events where location is incidental, old-school modules present spaces which players can freely navigate unrestricted by a plot. Movement in time versus movement in space.

- Manola, Joseph. 2016. “Conceptual density (or ‘What are RPG books for, anyway?’)”, Against The Wicked City. Many adventures do not offer anything which you cannot make up by yourself on the fly, whereas they should ideally serve to offer ideas you couldn’t have come up with.

- Whelan, Nick L.S. 2017. “Flux Space in Dungeons”, Papers & Pencils. Flux space represents the edges between nodes (locations) on a pointcrawl, which can also be elaborated upon as intersections between locales and as interactable areas in themselves.

- Hunter, Anne. 2018. “Sub-Hex Crawling Mechanics - Part 1, Pointcrawling”, DIY & dragons. An exploration of various ways to navigate the inside of a hex while exploring the overworld, this time focused on making pointcrawls inside of hexes.

- S., Brendan. 2018. “State of the art”, Necropraxis. There are many ways in which the OSR community has improved upon the conventions of play it has received from old rulebooks: quick character generation, minimal bookkeeping, and player-focused content (as opposed to materials used only by the referee).

- Hunter, Anne. 2018. "Two Good Links on Resource Management", DIY & dragons. A review of two posts about contemporary resource management, which (following "State of the Art") has become an emphasis of old-school play.

- Milton, Ben, Steven Lumpkin, & David Perry. 2018. Principia Apocrypha. An updated primer for principles of old-school play that reflects later developments since Finch's seminal primer.

- Hunter, Anne. 2019. “8 Abilities - 6, 3, or 4 Ability Scores?”, DIY & dragons. Although D&D and clones typically lists 6 ability scores, there is an implicit set of 8 (2^3) possible abilities based on 3 binaries: physical versus mental, force versus grace, and attack versus defend.

The above is, obviously, inexhaustive. You can refer to lists on Campaign Wiki (link), Necropraxis (link), Papers & Pencils (link), and Questing Beast (link) for more resources. From the selection, you can see an increasing depth and breadth of thought in how to run games considered to be old-school, and how the community increasingly developed its own solutions to problems posed either in practice or from the old rulebooks themselves. This is, in some respects, a different OSR than the one which had emerged on Dragonsfoot a decade or more prior; however, it is a movement which is in continuity with the desire to produce materials which align with the proposed play style of the community.

We're not in Greyhawk anymore.

This time was also marked by new book publications. These were not retroclones, but instead novel rulebooks whose rules were derived from the discourse taking place on G+ and blogs. They were also sometimes marked by auteur takes on the setting of the game. Chief among these was Lamentations of the Flame Princess (2011). Previously an imprint for new OSR-inspired adventure modules, such as Death Frost Doom, the titular rulebook was based off of B/X except with a heavy metal theme and some notable innovations (the d6 skill system and the ad hoc encumbrance system). Likewise, Dungeon Crawl Classics began as a line of new old-school adventures, but published its own self-titled rulebook in 2012 known for its peculiar types of dice beyond the typical Platonic solids. Also around this time were Dark Dungeons (2010), Stars Without Number (2010), Neoclassical Geek Revival (2011), Delving Deeper (2012), and Whitehack (2013), among others.

In August 2012, Timothy Brannan declared that the OSR was dead: if the original goal was to reintroduce and popularize some vision of old-school play to a general audience, then that goal was already accomplished [6]. The community would live on, he figured, but it needed a new set of goals to strive toward. Earlier, in January of that year, Tavis Allison also announced the death of the OSR [7]. Having achieved some level of mainstream success in publishing, the goal now is to expand the market for OSR publications without compromising vision (and also being weary of the failures of the traditional publishing model which Gygax and others took advantage of). He concludes: “The OSR is dead, long live the OSR!” What happened between Allison and Brannan’s declarations was the announcement of D&D Next in May 2012, the open play-test for what would be published as D&D Fifth Edition in 2014.

This is the ideal OSR rulebook. You may not like it, but this is what peak performance looks like.

A prominent blogger and self-styled leader of the 2010s OSR community was asked to consult on the new edition of D&D. Zak Sabbath created his blog D&D with Porn Stars in 2009, and rose to prominence with his web series on The Escapist called I Hit It With My Axe. Mike Mearls, a co-designer for D&D Next, wanted to take certain cues from the OSR for the new edition’s design: “The concept behind the OSR - lighter rules, more flexibility, leaning on the DM as referee - were important. We learned a lot playing each edition of D&D and understanding the strengths and weaknesses each brought to the table” [8]. Sabbath was brought in to consult on the old-school aspects of the new game, which originally included OSR preoccupations as turn-based procedure and wandering monsters. Although D&D Fifth Edition would become the representative of a new “neo-traditional” culture of tabletop games, prefigured by the likes of the actual play podcast Critical Role, it was initially celebrated as the long-awaited return of D&D to old-school tradition [5]. The blogger Dwiz from A Knight at the Opera collects many such comments at the time, such as one from ENWorld user Mike Tresca [9]:

OSR-style games currently capture over 9 percent of the RPG market according to ENWorld’s Hot Role-playing Games. If you consider the Fifth Edition of Dungeons & Dragons to be part of that movement, it’s nearly 70 percent of the entire RPG market. The OSR has gone mainstream. If the OSR stands for Old School Renaissance, it seems the Renaissance is over: D&D, in all of its previous editions, is now how most of us play our role-playing games.

Mike Tresca, ENWorld

Meanwhile, publications from the G+ side of the maybe-dead maybe-alive OSR were taking a different path, informed not by past editions of D&D but from their own tendency to reduce formal rules to as minimal a set as possible. The rationale was that this would facilitate improvised rulings by the referee, and encourage everyone to look beyond the book for how to interact with the game-world. Also, since Wizards of the Coast made old editions of D&D available for digital retail in 2012-2016, there was less of a worry about preserving the rulesets which were supposed to have first encoded old-school play; why make a retroclone when you can just buy the original? Publications became more experimental, as a result of all these factors and due to the inclinations of the community at the time. Many thus identify this period from ~2015 and thereafter as its own, distinct from the earlier years of the G+ community, characterized by increasing tangentiality and commercialism.

Into the Odd by Chris McDowall was released in 2015; it popularized one-roll combat where there are no to-hit rolls (a.k.a. attack rolls) but only rolls for damage which always succeed [10]. The Black Hack was released in 2016, which relied upon a single universal resolution rule (roll d20 equal to or less than some ability score) for all of its subsystems, from attacking to dodging to making saving throws; it also popularized the usage die for resource management, where consumables were depleted at random rates rather than kept track of on paper. Also released in 2016 was Ben Milton’s Maze Rats, originally a hack of Into the Odd to align with the typical fantasy D&D aesthetic (although it would later morph into its own unique ruleset). Milton would also publish Knave in 2018, a classless ruleset (or perhaps tool set) which popularized the slot inventory. These works were the seminal ultra-light rulebooks. Their lack of systematic treatment of old-school procedure would seem to contribute to the loss of that knowledge later, in favor of player-facing rules that were themselves kept to a minimum (and all other rules often implied at best).

The rulebook Mörk Borg is considered an example of 'artpunk'. It's a very pretty book!

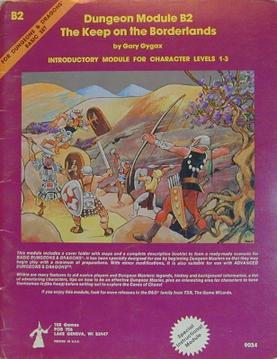

Other publications included Freebooters on the Frontier (2014), Shadow of the Demon Lord (2015), Best Left Buried (2018), Mothership (2018), Troika! (2018), Electric Bastionland (2019), Five Torches Deep (2019), Macchiato Monsters (2019), Mork Borg (2019), Old School Essentials (2019), and The Ultraviolet Grasslands (2019), among other titles and new editions of previous titles. Some of these rulebooks are retroclones, others are new takes on the dungeon crawl, and others are even more distantly related by being simply inspired by old-school principles (e.g. you might have a hard time running Keep on the Borderland using Mothership).

OSR became more akin to a vague marketing label (“It’s like porn: you know it when you see it!”) than a designation of backwards compatibility with respect to rules or even setting. However, it is difficult to draw a line at any point where one type of material was more highly regarded than others; Old School Essentials, for example, is now a very popular retroclone of B/X, and it exists alongside works like Electric Bastionland and The Ultraviolet Grasslands which are much further removed from the original D&D context. The only certain thing is that the OSR became increasingly commercial, and a greater volume of work was being published than ever before.

The End?

Nice Minecraft reference!

In December 2018, Google announced that they would be shutting down G+ in April 2019. Having served as a nexus for so much blogging and so many online campaigns during the 2010s, the OSR community built on that platform would become like a dying chicken running around with its head cut off. Someone more dramatic and annoying than myself might call this moment a collective trauma for the OSR community, not because it gave anyone post-traumatic stress disorder, but because it represents a certain rupture in the passage of knowledge and the reproduction of discourse.

Even now, there is no focal point for community discussion; blogs tend to be isolated from one another, and there are loosely-knit communities on Twitter, Reddit, and small forums. Many of the participants on those platforms have no idea of what had been done before; the store of cultural knowledge, despite still being online, is rendered inaccessible because of the lack of a community to propagate it. The online marketplace is perhaps the best way to get big ideas across now, especially with the increasing popularity of digital-only materials and their commercialization. Previously direct relationships between community members are now often mediated through indirect commodity exchange. This isn’t a moral issue; it is just how it is.

In 2019, the worse was to come. The month before G+ shut down, Zak Sabbath’s partner Mandy Morbid and three other women accused Sabbath of sexual assault and other abuses [11]. Wizards of the Coast removed Sabbath from the credits of Fifth Edition; Lamentations of the Flame Princess (the publisher) canceled all of Sabbath’s then-upcoming releases; Sabbath was also banned from many conventions and platforms for social media and RPG retail. This collapse led to many considering even the moniker ‘OSR’ to be soiled, now irreparably associated with violent scandal and rampant abuse (besides already being associated with the misogyny, racism, and homophobia of the right-wing elements of the community). It was certainly an end for some.

However, it is obvious that most people did not leave. Newcomers, unlike their predecessors, view themselves in discontinuity with the past, seeing the OSR as a specific community before their time rather than a body of knowledge still accessible to them (and still being developed to this day). There is still an increasing interest in commercial projects – a stated principle of one attempted, if forced, successor to the OSR called “SWORDDREAM” [12] – but there also are still bloggers writing posts in the depths of the internet, and deeper still there are grognards posting about good old AD&D and complaining about damn kids on forums few read anymore. I leave the task to someone else to figure out what new paths have been taken in the wake of all this.

Each contemporary group interested in the OSR play style identifies in some way with the OSR, or at least defines their identity relative to the OSR, but each one does so in different ways. Is the OSR a revival of playing AD&D or even some other TSR edition of the game? Is the OSR a renaissance of making new materials compatible with those old games, including modules and retroclones? Is the OSR a design movement guided by the same ethos of play as those early editions of D&D or other old tabletop games? Is the OSR like porn, in that you know it when you see it? Rather than saying these definitions are all a little bit right, I claim that they are all wrong: not because there is a true definition of the OSR, but because the OSR has no definition. The existence of any supposed OSR is predicated on an imagined relationship to the past, a false history to which it lays claim.

Identity Formation in the OSR

Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations [13] weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living. And just as they seem to be occupied with revolutionizing themselves and things, creating something that did not exist before, precisely in such epochs of revolutionary crisis they anxiously conjure up the spirits of the past to their service, borrowing from them names, battle slogans, and costumes in order to present this new scene in world history in time-honored disguise and borrowed language. Thus Luther put on the mask of the Apostle Paul, the Revolution of 1789-1814 draped itself alternately in the guise of the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire, and the Revolution of 1848 knew nothing better to do than to parody, now 1789, now the revolutionary tradition of 1793-95.

Marx, 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte

I promised an “object-oriented” history of the OSR. If there was nothing particularly special (i.e. jargony) about the above, it’s because there’s nothing special about object-oriented ontology. There is, obviously, some continuity between different communities that had identified with the term ‘OSR’; there had to have been at least enough continuity to pass on the term, even it was appropriated without rhyme or reason (unlikely). Yet there are also breaks in the different communities that identified as OSR, with respect to their aims, ideology, and even demographics. Is there anything wrong with saying these breaks, represented by different broad groups, are simply different? It oversimplifies things.

An OOOSR, or Many of Them?

The metaphysics of a personal pan pizza.

Graham Harman would argue that each such individual OSR constitutes a distinct and discrete ‘object’ or ‘thing’. This is not just because of what we might consider the different constituent parts of an OSR (community, aims, ideology), but because of how each OSR exceeds the sum of those parts. For another example, Harman says that Pizza Hut has a reality which exceeds any pizza box, employee, franchise or even the sum thereof. The mere notion of Pizza Hut is an object that enters into relationships with all those other objects, and is in that sense just as real. This view is useful to understand each instance of an OSR object on its own terms, seeing each as a particular occurrence with its own context rather than having to locate each in a history of one true OSR or on a spectrum of OSR-ness. It is supposed to treat the objects with some dignity of their own, rather than always in a relationship with some other, arbitrarily privileged, object. What does it matter that one OSR is less OSR than some other OSR? Instead, why not talk about those things as both deserving an equally specific treatment?

The problem with object-oriented ontology is that it takes for granted the reality of these objects. Harman identifies as an immaterial realist: he sees objects as having a reality which is merely expressed, not determined, in interactions with other objects. Harman sees the reality of objects as something which is denied by language on a structural level, because signifiers reduce real objects either to their parts or to their whole. Either way, the full picture presented by language is an incomplete representation of the reality of objects. Harman’s insight is not an unusual one; when considering language, we are often confronted with its failure to adequately communicate or represent things. Yet it is precisely the apparent discreteness of things, or difference between things, which language assumes in order to create meaning and to distinguish things through itself. Where Pizza Hut exists beyond being a corporate entity (which is distinct from Pizza Hut as an idea, as per Harman), it is merely a signifier which makes it easier for us to discuss the corporation and things related to it. Likewise, there is one or more ideas of an OSR which exist alongside distinct communities which latch onto the OSR as a label for themselves. Harman’s error is in assuming that the reality supposed by language actually exists, when it is indeed a reality assumed (and thus created) by language in order for language to have something (i.e. signifiers) to talk about.

The OSR is definitely a signifier, a label or moniker or word for something (a “signified”); it is also a signifier whose signified, obviously, no one can agree upon because so many different groups of people have assigned it different meanings to their own ends. An “object-oriented” history of the OSR is thus tantamount to a naive history thereof: we can suppose as many distinct and discrete OSR objects as we’d like, but it does not change the fact that their identification with the OSR is an ideological point rather than a point of reality. More specifically, the assertion of an old-school revival or renaissance hinges on a supposed past. The goal of an OSR proper then is to return to that (apparent, idealized, fictional) prior state of things, whatever it is or whatever that return entails. At best, an object-oriented approach can treat this past ideal as yet another object (or multiple objects) with which various OSR movements interact. So what? What is this past ideal, how does it relate to particular OSR movements, and how is this discourse between ideal and reality structured? These are questions which an object-oriented approach, by fetishizing a reality of objects rather than asserting a strict unreality thereof, obscures rather than sheds light upon.

With all this in mind, we can proceed to analyze the OSR for what it is, insofar as it is an ideal rather than any one group of people and work: a whole lot of hubbub over nothing.

Nostalgia and Identity

Oh, yeah, you're a real old-school gamer? Well, I've killed orc babies!

Those first grognards were very simple in what they wanted. They didn’t like the new Third Edition or, really, anything published since Gygax’s departure from TSR. They just kept playing the games they had already been playing since the late 70s-80s, hoping that one day Wizards of the Coast would see the error of their ways and eventually published refreshed editions of those same games. At first glance, there is not much going on with these folks on a productive level; any materials being made were mostly adventure modules and maybe house rules, rather than any introspective work on what exactly they liked about these games or what they wanted to see more of. They didn’t need more. However, there were already the seeds of an OSR identity taking hold. When the words “old school revival” were first typed, they could not be taken back. There now existed a moniker with which people could identify, and in doing so they could identify their own desires with those of a whole group of people. This very identity rested in a past state of affairs, the golden age of D&D, and a desire to return there. It’s not that nostalgia is inherently grounded in falsehood (as much as it tends to be), but that nostalgia seeks to affirm its own ideal history regardless of its truth-value. There is nothing immediately suspect about this past ideal, seeming perhaps fair enough and grounded in what might as well be real. Wizards of the Coast, certainly, wasn’t publishing anything like AD&D anymore; surely, some people missed it.

There was some trouble, however, when a proper play culture began developing around the burgeoning OSR community. The OSR play style was propagated on the belief that it was a return to a Gygaxian ethos of play and, indeed, this is the only premise for such a culture to take hold in a community that yearns to return to an idealized past. However, as per The Retired Adventurer, the OSR play style is at odds with many hallmarks of “classic play” as propagated by Gygax himself [5]. For example, Gus L. argues that we owe D&D as an exploration game not to Gygax, whose tendencies aligned more with formal war game conventions, but to Jennell Jaquays and her immersive adventure module Caverns of Thracia (1979) [14]. In particular, Jaquays originates the idea that secret doors can be investigated in-universe ("diegetically") as opposed to rolling the dice. Such diegetic interactions with the game-world are encouraged by Finch's Primer, but are not grounded in some monolithic play style of the 1970s, much less one propagated by Gygax who wrote the self-styled authorative rulebook for D&D. Overall, in comparison with Gygaxian play, the OSR overemphasizes player skill and deemphasizes game balance, and it also discourages direct engagement with formal rules in favor of diegetic interactions with the game-world mediated (and improvised) by the referee. The history supposed by the OSR is an imagined history which contradicts the actual past in service of an ideal.

We can consider nostalgia not as something inherently problematic, but more broadly as an unreliable expression of a fantasy. The French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan insisted that the unconscious is structured like a language, meaning that the unconscious is ruled over by a set of symbols and the relationships governing those symbols like a grammar would for words. Lacan reframed Sigmund Freud’s notion of the Oedipus Complex as something unrestricted to the literal figures of mother and father. To make it simple, the Oedipus Complex is the hypothesis that a (male) child is prevented from having an exclusive relationship with his mother due to interference from his father; because the mother is rendered thus inaccessible, the child is forced to give up on the mother and to instead pursue substitutes for the enjoyment he had once received from his mother. Meanwhile, the character of these substitutes is modeled after the child’s own relationship to his mother as well as to his father; the child thus internalizes gender roles, sexuality, and other incidental things. Lacan argued instead that the Oedipus Complex is not really about mothers and fathers, then, but about one’s own relationship to desire and the ‘language’ in which it is articulated. The experience of (perceived) loss can lead to trauma for a person; this trauma can structure that person’s subsequent lived experience, informing how they behave, how they think, and what they desire. Lacan’s work is thus intimately related to nostalgia, as the perceived loss of a past rendered inaccessible, and which is then sought after to no avail. Nostalgia, for individuals and for collective identities, is therefore always a fantasy in service of a desire, rather than the desire itself.

The banner of old-school play was upheld by too many groups with too many desires which overlapped and contradicted and crossed paths and diverged again. None of them held onto the banner because it was necessarily accurate for themselves or because they were its rightful owners, but because the banner is a signifier of a desire to return to the past (before it was wholly a self-referential indicator of OSR-ness). As such, it doesn’t really signify anything as much as it act as an ideological rallying call to return to some tradition. This holds as true for the AD&D grognards as it does for the G+ bloggers, or those who uncritically believed and propagated the myth of old-school play. It holds true now for those who look at the OSR as a bygone era, simultaneously as a reference point for their own identity and as a corpse ripe for the picking. As Sivaranjan tells the rest of us sometimes, “I’m still here!”

Conclusion

Each proclamation of the OSR’s death relies upon a particular definition of the OSR. When the OSR “died” in 2012, it was because the community had attained the level of success it had always strove for; the old school was finally revived. When the OSR “died” in 2019, it was because a significant platform was deleted from the internet, and because of abuses which had rocked the community to its core. Yet it was only a death to those who looked at the ruin afterward and saw all that had been forgotten since, with no one to restore it to yet some other dubious past state; at the same time, most of the people who were there were just dispersed elsewhere, still doing their own thing on odd corners of the internet. Will the OSR really die, if it hasn’t yet? Well, which OSR, and in which way? These are not neutral claims, and any answer reveals much more about one’s relationship to a community (or lack of one) and its ideal, rather than anything about the OSR as such (especially as a play style). This is true whether you think the OSR has died or is still alive.

You cannot stop people from identifying with the OSR. At this point, it is synonymous with the specific culture of play that was originated and cultivated by players who had themselves identified with the term (and whose body of knowledge has been rendered, to many, inaccessible). Nor can you stop people from playing the way that is most often described as OSR; obviously, it’s one of the ways I like to play also. However, it is concerning to see the myth of the OSR be propagated, especially to arbitrarily decide at what point some true OSR community or movement had ceased to exist. As a play style, the OSR has not gone away and will not go away for a long time. Another term might be more descriptive, but that’s not for any one person to decide.

As an empty signifier of some relationship to the past, it is easier to say that the OSR has always been dead. Early on, grognards donned the costumes of Gygax and (less often) Arneson. They thought that the past had been forgotten, confusing it for their new history. Now, we don the costumes of grognards. The longer the OSR ‘lives’, the more dead it becomes. Let’s drop the act.

Let it die.

Edit: I wrote an addendum (link)! I have also expanded upon the list of blog posts on a new page (link).

Works Cited

[1] B., Marcia. 2021. “Critique of the Conversation Surrounding Lyric Games”, Traverse Fantasy.

[2] Maliszewski, James. 2008. “What’s a Grognard?”, Grognardia.

[3] Maliszewski, James. 2009. “Full Circle: A History of the Old School Revival”, The Escapist.

[4] Finch, Matthew J. 2008. A Quick Primer for Old School Gaming.

[5] B., John. 2021. “Six Cultures of Play”, The Retired Adventurer.

[6] Brannan, Timothy. 2012. “Is the OSR dead?”, The Other Side.

[7] Allison, Tavis. 2012. “The OSR Has Won, Now What Does It Stand For?”, The Mule Abides.

[8] Mearls, Mike. 2012. “AMA: Mike Mearls, Co-Designer of D&D 5, Head of D&D R&D,” /r/rpg on Reddit.

[9] Dwiz. 2021. “The New School, the Old School, and 5th Edition D&D”, A Knight at the Opera.

[10] This is a simplification: since armor subtracts from the number of hit points lost to damage, there is the possibility of losing 0 hit points if one is wearing armor.

[11] Arndt, Dan. “New Allegations Against Zak Smith Spotlight Rampant Harassment In The RPG Industry”, The Fandomentals.

[12] 2019. Nine Principles of the Sword Dream.

[13] See Gus L.'s later blog, All Dead Generations, which takes its name from that quotation of Marx.

[14] L., Gus. "Spectral Interrogatories III - Caverns of Thracia", Bones of Contention.

Thanks for pulling this together - especially for that mighty collection of influential posts.

ReplyDeleteI feel when I came upon the OSR (~2014, before its second dying) it already seemed to require a huge amount of knowledge of references, background, etc. that I bounced off it. Only when the bones were lying around ~ 2017 onwards was it possible to really pick over everything and get a grip on what was there. So, good that it 'died' for a while - it meant things were still enough that one could catch up.

i think that's a comforting way to look at it! :) after all there's so much to read, it'd probably take a couple of years to get through what's been written in one (not to mention, hindsight is 20/20 in terms of what proves influential in the long run)

DeleteThat is not dead which can eternal lie, and with strange eons even the OSR may die.

ReplyDeleteI still love what Patrick "False Machine" said: “I think the OSR as I knew it is basically a ruin, and its a strange moldering ruin in the swamp that other people from future gaming societies come to delve for its weird secrets. And they come to speak to the wizards and cackling ghouls that inhabit that ruin.”

ReplyDeletehehe i love that!!

DeleteClearly what we need is OSR 2nd Edition.

ReplyDeleteOne might also mention the "grotty" aesthetic that was shared and played with on a lot of OSR blogs in the 2010s, which had little if any precedent in Gygaxian times. It was a fun and original aesthetic created by an online social scene/workshop of ideas that identified, accurately or not, as old-school. You wouldn't mistake that stuff for anything published in 1974 or 1980.

ReplyDeleteMy feeling is that if the OSR is/was a group of creative bloggers, then it doesn't matter to me if they're no longer all following the same definitions. I always took a salad bar approach to their creations anyway, taking only what I wanted, and I'll continue to do so. If the OSR is/was an online social group, then it REALLY doesn't matter to me whether it continues as it was. There was plenty of toxicity there from the beginning (gatekeeping, bullying, picking fights with other groups, et al.). But more importantly, blogging and Google+ posts can't be more important to what the OSR is or was than actual playing of RPGs. That would be kind of silly.

And if the OSR is/was people actually playing games in an old-school style, then surely nothing about the state of these blogs can matter that much. Even the most influential and productive blogger is just a blogger, and no one needs them in order to play, to be creative, or to be old school however they see fit. For me, if anything defines old-school play, it's DIY, the old spirit of filling in a pad of blank graph paper, and that's not going anywhere.

I am both more dramatic and more annoying than you, having absolutely referred to the end of Google+ as a collective trauma for the scene. :P

ReplyDeletei'll do my own self-slander but i won't stand for yours!

DeleteThanks, very nice. Lacan, even!

ReplyDeletethank you! glad you liked it :)

DeleteLoved that article! I was hoping someone smarter than I am would point out at that collective re-inventing of the wheel samsara cycle thing that's been going on for seemingly forever. Great collection of Important BlogPosts (tm) too!

ReplyDeleteAs I've been meaning to say for some time - nostalgia is as you note largely harmless or psychologically beneficial for the individual, but group based nostalgia is often the opposite. It often seeks to restore the imagined, believing some idealized version of the past (without guilt, errors, or failures) is objectively true.

ReplyDeleteThis kind of restorative nostalgia is also a profoundly and poisonously effective way to create group identity - especially once it becomes more focused on the nóstos (Homeric homecoming) then the álgos (pain/loss). One can tap into peoples' anxieties and the emotional soothing that nostalgia provides for them, while encouraging action to restore the imagined false past. Of course there is no real possibility of return to a made up idealized past - so someone has to take the blame, and it won't be the nostalgics.

As noted by many psychologists and political theorists (and studied fairly well - William Kurlinkus' breakdown of the rhetorical structure is especially interesting) that collective/restorative nostalgia depends on declaring the idealized past as truth and creating an outgroup or enemy to blame for both the fundamental nostalgic rupture and inability to return to it, the desired home. Personally I like Boym's distinction between restorative (nóstos) focused nostalgia and reflective (álgos) focused nostalgia. The first makes us angry that no one in Ithaca recognizes our aged, bald self, pushing us towards a deadly archery spree (at least metaphorically). The second is about reflecting on loss and the faults of memory and so it can encourages us towards revising our views of the present and the future in hopeful ways.

How does this apply to RPGs? Well it makes me wary of people claiming the banner of the OSR to build identity around alleged past truths or use it to attack others' works and play styles. It's not just that these louts are annoying (and often victims/fans of other less inconsequential restorative nostalgia). It's also because they tend towards categorical mistakes, survivor bias, ossification, dogmatism, hagiography, and a profound lack of reflection when it comes to older RPG work.

That blog post is absolutely amazing! Thanks for coming up with all that work, Marcia. Big fan!

ReplyDeleteCan I translate this blog post to portuguese? I bet the brazilian community would love that. =)

hi rafael, thank you for your kind words :)) you are totally welcome to, thank you for asking!

DeleteI read Balbi's translation. Thanks to the two comrades.

Deletethank you again, balbi!!!

DeleteBrazilian passing by just to say that you write very well, comrade B. Thank you. I'll go read the addendum. Until.

ReplyDeletehello xikowisk, thank you very much! 😊 i'm glad you found it interesting!

DeleteI wanted to point out that the tragedy that befell the community at the hands of Google can happen to any forum/platform used if you can't easily pull backups that can then be usefully used after your chosen forum/platform goes out of service.

ReplyDeleteThere needs to be archiving and content generated and created in portable ways. If there is a heirarchy that needs to be provided between pages or articles, there needs to be a way to capture that.

This could happen to everyone in Reddit too. Lots of great stuff that we tend to, as users or even contributors, assume it will always be there despite we know darn well it might not. There's no clear sense of urgency to prepare for the day the walls will fall.

And thus, many great bits of work are lost. It's like we enjoy watching the Library of Alexandria burn down very 4 or 5 or 7 years.

There's a lot more to say about this great article, but let's also say that any community wanting to create and share really great (or funny) things about a topic needs to have a plan to keep that information available after the current host vanishes.

Did archive.org record any of the Google+ sites?

DeleteOnly in the last ca. two years have I wandered the various still existing OSR-ish blogs. However, I never spent time in the Google+ scene, mainly because I was just playing whatever my friends ran. Only when I started to feel guilty that I ran my last game ca. 2007, and started to run a game again, did I delve into these still rich ruins.