The OSR Should Die: Basic Edition

This is a revision of my 2022 blog post, shortened for publication in Knock! and also for clarification.

Is the OSR dead yet? If you asked some, they would say yes. There was a body of cultural knowledge which has been rendered inaccessible (for some reason) to hobbyists who are working in the same space. What is old is new again, so people are talking about random encounters and reaction rolls as if they had discovered them themselves like Christopher Columbus discovering the Americas. They weren’t the first ones there and, if you were to ask Ramanan Sivaranjan from the Save Vs. Total Party Kill blog, no one had left either. The OSR is not dead because he’s still there, as are others from the time of G+ who are also still doing their own thing. How can something be dead and alive at the same time? It could be a difference of definitions. It could also be a zombie.

An authoritative definition of the OSR is difficult to arrive at because any one definition is sure to attract contention from groups that self-identify with the term. These parties are not necessarily mutually exclusive with each other, but they tend to embody particular perspectives on the term owing to their different time periods, social networks, or activities (including play, communication, and organization among other factors). Trying to invent or assert a definition of the OSR is itself participating in the discourse surrounding the OSR. It’s self-referential and, often, self-serving. It is worthwhile, instead, to consider the multiplicity of the OSR as an empty signifier (i.e. a signifier that signifies nothing), to understand why people try to answer the question, “What is the OSR?” In doing so, we can criticize not just the apparent existence of a singular and true OSR, but also the role that the mere term ‘OSR’ plays in establishing collective identities through false imagined histories.

A history of anything is always going to be biased towards one view than another. Therefore, I will not consider the history of a particular OSR or an offshoot thereof, but of the term ‘OSR’ and to what it has been applied. Then, I will address what I believe is the real question at hand: not when the ‘real’ OSR started and ended, but why that term (‘the OSR’) has been adopted by different groups with different interests and relations to the hobby: hardcore AD&D players, DIY D&D bloggers, or commercial book publishers.

2000-2009

"We have AD&D at home."

The term “old-school revival” or “old-school renaissance” originated in the early 2000s. It was used mainly by players of Advanced Dungeons & Dragons on the fan website Dragonsfoot. Dungeons & Dragons, Third Edition had just been published by Wizards of the Coast, and it represented—or perhaps imposed—a new direction of play for the Dungeons & Dragons brand (albeit one which had been anticipated with the release of supplements for AD&D Second Edition, especially Combat & Tactics). Meanwhile, Dragonsfoot published materials for ongoing AD&D campaigns, and those who felt left behind by Wizards of the Coast or even the post-Gygax TSR (the original publishers of D&D) found a new home. However, many feared that without official support, the player base for these defunct games would dwindle and all would be forgotten.

Third Edition posed a problem, but also a solution. Owing to the promiscuous Open Game License (OGL) originated by Wizards of the Coast for their new game, Dragonfoot’s OSR community was enabled to publish retroclones which either faithfully reproduced the rules and mechanics of early D&D rulebooks, or remixed them to agree more with Third Edition’s d20 system: Castles & Crusades (2004), OSRIC (2006), Basic Fantasy RPG (2007), Labyrinth Lord (2007), Swords & Wizardry (2008). This is the end of the story for some, perhaps exemplified by Gary Gygax's death in 2008.

Yet, for others, it was a beginning. James Maliszewski began his Grognardia blog in 2008. His first post was a copy of the OGL, declaring all materials on his blog to be under that license. His second post was called, “What’s a Grognard?”, where he lays out the mission statement of his blog:1

RPG grognards are popularly held to be fat, bearded guys who go on and on about how things were better “back in the day” before “the kids” ruined everything. I don’t think the history of roleplaying games since 1974 has been one of continual decline, but I do think a lot of good stuff has been lost or at least forgotten since then. One of the purposes of this blog is to discuss that good stuff and its importance for and applicability to the hobby today.

James Malizewski, “What’s a Grognard”, 2008.

Maliszewski argued elsewhere that the OSR “has no grand unifying principle beyond a love […] for RPGs, particularly Dungeons & Dragons” (and its older editions), but rather than being a reactionary ‘revival’, it included the creative force of a ‘renaissance’.2 He said many people who identified with the OSR are just playing the way they want to play, and doing it themselves (“DIY”) rather than receiving that play style from a book sold to them. This is best represented by Matthew J. Finch’s A Quick Primer for Old School Gaming, which outlines principles such as: rulings, not rules; player skill, not character skill; heroes, not superheroes; and forgetting game balance.3 Many of these maxims contradict the ethos of TSR-sanctioned play and reject the advice Gygax gave in Advanced D&D. Regardless, because of the movement’s fervor to establish itself, there were materials being made that were not retroclones but, instead, wholly new works that (apparently) share an ethos of design with those old D&D editions. The OSR was still in its infancy, Maliszewski concludes, and whether it would result in a renaissance proper was then yet to be seen.

Maliszewski’s article is not without rose-tinted glasses. John B. from The Retired Adventurer regards the old school renaissance as “a romantic reinvention, not an unbroken chain of tradition”.4 This may be attributed to a shift in focus somewhere between 1999 and 2009, from continuing to play AD&D to playing according to a specific style which was then theorized about on blogs et cetera. It is not a total discontinuity, however: early on, the early members of the self-identified OSR took a DIY approach because their play styles were no longer supported by official publications of D&D. Being a movement centralized on one platform, it did not take long for one play style to predominate that community’s culture. All the while, this play style has the appearance of something rediscovered rather than something created, with legitimacy derived from this apparent tradition.

There is no point in arguing where a line should be drawn in time between a ‘real’ OSR and a ‘false’ OSR in 2000-2009, or between a so-called revival and renaissance. This is not only because many of the same people participated in the OSR up to 2009 and beyond, but because the tendency of the OSR to become a ‘movement’ and a ‘culture’ existed at its inception. Its origin was, strictly speaking, nothing new: it was AD&D players (less often of other editions) reminiscing about publications for D&D before Third Edition, or even before Second Edition. The production of cultural materials by this community, whether forum threads or blog posts or rulebooks, necessarily culminated in a renaissance, as the act of creation and introspection results in something new informed by past and present. The unifying principle of the OSR at any point is nostalgia for a lost ideal, the reality of which was never lost but was instead constantly in the process of being created in hindsight.

2010-2019

In 2011, Google released the social network Google+ or G+, where users interact in specific groups or communities rather than always addressing a whole mass of “friends”. G+ interfaced with the blogging platform Blogger, which Google acquired earlier in 2003. What better way to discuss the hobby, share blog posts, and organize campaigns online? G+ therefore became a hub of activity as the OSR outgrew the Dragonsfoot forums, in size and in ideology. The earlier OSR, being a revival of interest in AD&D, was already overshadowed in years prior by an interest in other editions of D&D and a desire to realize the ideas they (apparently) encoded. The G+ community grew out of this context and produced much of the common wisdom we now often take for granted. It elaborated upon the OSR as a play style, rather than as a revival of appreciation for TSR literature. This is the era many identify as the OSR proper (or, rather, the time to have been there), especially those who participated in it. I've compiled many seminal blog posts on the Keystones page of my blog!

This time was also marked by new book publications. These were not retroclones, but instead novel rulebooks whose rules were derived from community discussions. They were sometimes marked by auteur game settings. Chief among these was Lamentations of the Flame Princess (2011). Previously an imprint for new OSR adventures, such as Death Frost Doom, the titular rulebook was based off of B/X with a heavy metal theme. Likewise, Dungeon Crawl Classics began as a line of new old-school adventures, but published its own self-titled rulebook in 2012. Also around this time were Dark Dungeons (2010), Stars Without Number (2010), Neoclassical Geek Revival (2011), Delving Deeper (2012), and Whitehack (2013), among others.

In August 2012, Timothy Brannan declared that the OSR was dead. If the goal was to reintroduce and popularize some vision of old-school play to a general audience, that was already accomplished.5 The community would live on, he figured, but it needed new goals. Earlier, in January of that year, Tavis Allison also proclaimed the death of the OSR.6 Having achieved some mainstream success in publishing, he saw the new goal as to expand the consumer market for OSR publications without compromising vision (while also being wary of the failures of the traditional publishing model which Gygax and others took advantage of). He concludes: “The OSR is dead, long live the OSR!”

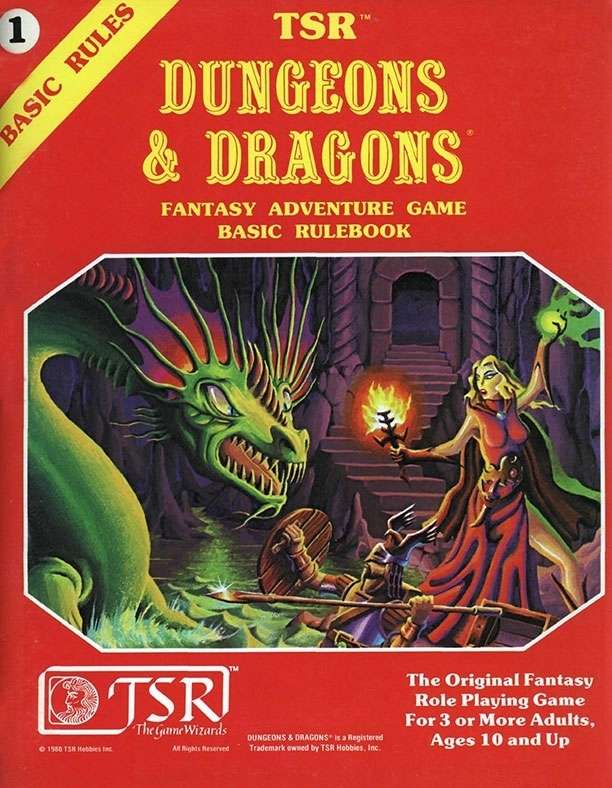

This is the ideal OSR rulebook. You may not like it, but this is what peak performance looks like.

What happened between Allison and Brannan’s declarations was the announcement of D&D Next in May 2012, the open play-test for what would be published as D&D, Fifth Edition in 2014. Mike Mearls, one of its lead designers, wanted to take cues from the OSR for its design.7 Although that edition became the prototype of the “neo-traditional” gaming culture, as prefigured by the popular podcast Critical Role, it was first celebrated as the long-awaited return of D&D to the old-school tradition:8

OSR-style games currently capture over 9 percent of the RPG market according to ENWorld’s Hot Role-playing Games. If you consider the Fifth Edition of Dungeons & Dragons to be part of that movement, it’s nearly 70 percent of the entire RPG market. The OSR has gone mainstream. If the OSR stands for Old School Renaissance, it seems the Renaissance is over: D&D, in all of its previous editions, is now how most of us play our role-playing games.

Mike Tresca, ENWorld, 2015

Meanwhile, publications on the G+ side of the maybe-dead maybe-alive OSR were taking a new path, informed not by old D&D but from a tendency to reduce formal rules to be as minimal as possible. The idea was that this would facilitate rulings by the referee, and encourage players to look beyond the book to interact with the game. Since Wizards of the Coast made old editions of D&D available digitally starting in 2012, there was also less of a worry about preserving the original (allegedly) old-school rulebooks. Why buy a retroclone when you can buy the original? Publications became more experimental, with Into the Odd (2014), The Black Hack (2016), and Knave (2017) being chief representatives. Many thus identify this period from ~2015 and thereafter as its own, distinct from the earlier years of the G+ community, characterized by increasing tangentiality and commercialism.

It's the end of the world as we know it!

OSR became more akin to a vague marketing buzzword than a marker of backwards compatibility with TSR-era D&D. However, it is difficult to draw a line at any point where one category was more highly regarded than others. Old School Essentials (2019), for example, a popular retroclone of B/X, exists alongside Electric Bastionland (2019), Mörk Borg (2019), and The Ultraviolet Grasslands (2018) which are further removed from the OSR’s original context. The only certain thing is that the OSR became increasingly commercial, and more work was being published than ever before.

2020+: The End?

In December 2018, Google announced that they would be shutting down G+ in April 2019. Having served as a nexus for so much blogging and so many online campaigns during the 2010s, the community built on that platform would become like a chicken running around with its head cut off. One might call this moment a collective trauma for the OSR community, not because it gave anyone PTSD, but because it represents a rupture in the passage and reproduction of cultural knowledge.

Now, there is no focal point for community discussion. Blogs are more isolated from each other, and there are loosely-knit communities on Twitter, Reddit, and small forums. Many participants on those platforms have no idea of what had been done before. The store of cultural knowledge, despite still being online, is rendered inaccessible for lack of a community to propagate it. The marketplace is the best way to get big ideas across now, especially with the popularity of digital materials and their commercialization. Previously direct relationships between community members are now often mediated through indirect commodity exchange. This isn’t a moral issue; it is just how it is.

Many members of the G+ community yet did not abandon their blogs, no more than Dragonsfoot users abandoned the forum when G+ came on the scene. Newcomers, not unlike their predecessors, view themselves in discontinuity with the recent past, and see the OSR as a long-gone community rather than one still accessible to them and still being developed to this day. There is an increasing interest in commercialization, a stated principle of one attempted successor to the OSR called SWORDDREAM, but there are still bloggers blogging blogs, and grognards still complaining about damn kids on forums few read anymore.9

Each group interested in the OSR play style identifies in some way with the OSR, or at least defines their identity relative to the OSR, but in different ways. Is the OSR a revival of AD&D or some other TSR edition of the game? Is it a renaissance of new materials, such as adventures and retroclones, compatible with those old games? Is it a design movement guided by the same ethos of play as early D&D? Is it like porn, in that you know it when you see it? Rather than saying these definitions are all correct, I claim that they are all wrong: not because there is a true definition of the OSR, but because the OSR has no definition. The existence of any supposed OSR is predicated on an imagined relationship to the past, a false history to which it lays claim.

Those first grognards were very simple in what they wanted. They didn’t like the new Third Edition or, really, anything published since Gygax’s departure from TSR. At first glance, there is not much going on with these folks on a productive level. Any materials being made were mostly adventures and house rules, rather than any introspective work on what they liked about these games or what they wanted to see more of. They didn’t need more than that. Why would they?

Yet the seeds of an OSR identity were already taking hold. When the words “old school revival” were first typed, they could not be taken back. Thereafter existed a moniker with which people could identify, and in doing so they could identify their own desires with those of a whole group of people. This very identity rested in a past state of affairs, the golden age of D&D, and a desire to return there. It is not that nostalgia is inherently grounded in falsehood (as much or as often as it tends to be), but that nostalgia seeks to affirm its ideal history regardless of its truth-value. The history of D&D supposed by the OSR is an imagined one which contradicts the game’s past in service of an ideal.

The banner of ‘OSR’ was upheld by various groups whose desires overlapped, contradicted, crossed paths, and diverged again. None of them held onto the banner because they were its rightful owners, but because the banner is a signifier of a desire to return to the past (before it became wholly a self-referential indicator of OSR-ness). This holds as true for AD&D grognards as it does for many G+ bloggers. It even holds true now for those who look at the OSR as a bygone era, both as a reference point for their own identity and as a corpse ripe for the picking. As Sivaranjan says, “I’m still here!”

Conclusion

Each proclamation of the OSR’s death relies upon a particular definition of the OSR. When the OSR “died” in 2012, it was because the community had attained the success for which it had striven: the old school was finally revived. When the OSR “died” in 2019, it was because a significant platform was deleted from the internet. Yet it was only a death to those who looked at the ruin afterward and thought all that had been forgotten since, with no one to restore it to yet some other past state.

At the same time, most of the people who were there were just dispersed elsewhere, still doing their own thing on odd corners of the internet. Will the OSR really die, if it hasn’t yet? Well, which OSR, and in which way? These are not neutral claims, and any answer reveals much more about one’s relationship to a community (or lack of one) and its ideal, rather than anything about the OSR as such (especially as a play style). This is true whether you think the OSR has died or is still alive.

You cannot stop people from identifying with the OSR. It is synonymous with a culture of play that was originated and cultivated by players who identified with the term. Nor can you stop people from playing the way that is most often described as OSR. However, it is concerning to see the myth of the OSR be propagated, especially to arbitrate at what point some true OSR movement had ceased to exist. As a play style, the OSR has not gone away, and will not go away for a long time. Another term might be more descriptive, but that’s not for any one person to decide.

As an empty signifier of some relationship to the past, it is easier to say that the OSR has always been dead. Early on, grognards donned the costumes of Gygax and (less often) Arneson. They thought that the past had been forgotten, confusing it for their ideal history. Now, we don the costumes of grognards. The longer the OSR ‘lives’, the more dead it becomes. Let’s drop the act.

Let it die.

Postscript

To reiterate, I cut down this article with help from Joshua McCroo (thank you!!) to contribute to the Knock! magazine. This was a good opportunity to trim off the original post’s fluff. The tangents on object-oriented ontology and Lacan went over people's heads, such that one popular response to the article—although the author admitted his misunderstanding in the comments—thought that I was using OOO as a basis for my argument, rather than me using it to construct a false argument that I then criticized. It's my blog, not yours, but it was a good reason to revisit this post and make the specific critique crystal-clear. I should probably write a separate post one day to complain about OOO, since using the OSR to complain about it and vice versa didn't pan out. Just a little confusing!

To abridge my addendum:

My view is neither that the OSR is dead, nor that the OSR is alive, because both of those answers try to grasp at a question ("Is the OSR dead?") which is itself 'politically' loaded with ideas about what constitutes the OSR as a play style, a community, or an ideology. My post is titled "The OSR Should Die" precisely because, in many respects, the OSR is not dead; specifically, the founding myth of the OSR tends to be alive and well.

The quality of being neither dead nor alive is something which lends the OSR, as a signifier, a zombie-like quality. The "old school" is a myth; if you can dictate the myth, you can dictate the OSR. If we instead embrace the OSR as being basically nonsensical, embracing the acronym as a self-referential signifier instead of believing the myth which it stood for ("old-school"), we can give ourselves more flexibility and also view our hobby more critically.

If you didn't want to read all that, just look at the title of the post. It's not called "The OSR Is Dead", but "The OSR Should Die". It's a bit dramatic, I know, but it was my attempt to bypass the debate on the status of some OSR and to pose a different question instead: aren't you tired of being restrained by the same cyclical discourse about the OSR? Don't you just want to go ape-shit?

Hope this helps!

One more thing: the cover illustration for my 1974 retroclone Fantastic Medieval Campaigns is based off of this article. That's a dead guy!

Maliszewski, James. 2008-03-30. “What’s a Grognard?”, Grognardia. ↩︎

Maliszewski, James. 2009-08-20. “Full Circle: A History of the Old School Revival”, The Escapist. ↩︎

Finch, Matthew J. 2008. A Quick Primer for Old School Gaming. ↩︎

B., John. 2021-04-06. “Six Cultures of Play”, The Retired Adventurer. ↩︎

Brannan, Timothy. 2012-08-21. “Is the OSR dead?”, The Other Side. ↩︎

Allison, Tavis. 2012-01-06. “The OSR Has Won, Now What Does It Stand For?”, The Mule Abides. ↩︎

Mearls, Mike. 2012-11-03. “AMA: Mike Mearls, Co-Designer of D&D 5, Head of D&D R&D,” /r/rpg on Reddit. ↩︎

Dwiz. 2021-09-12. “The New School, the Old School, and 5th Edition D&D”, A Knight at the Opera. ↩︎

Graham, Jack. 2019. The Nine Principles of the *DREAM. ↩︎

Comments

Post a Comment